Because my research has focused on the neuroscience of rehabilitation for several decades, I have received hundreds of email messages, letters and telephone calls from parents and grand-parents desperately seeking help for their brain-damaged or developmentally-impaired child or grand-child. Because the losses suffered from brain injury and developmental disabilities expressed in this correspondence is usually daunting, and because it is so difficult to understand their nature and their true neurological and experiential origins at a distance, it is usually impossible to provide significant help. Because I am remote from the child’s and their familys’ struggles, I also know that I generally do not really fully appreciate the anxieties and distresses and frustrations that they must be experiencing.

This was brought home to my wife Diane and me when my daughter Betsy’s 4-year-old niece (her husband’s sister’s child) accidentally hung herself with a jump-rope when she fell off of a playground slide out of view of her caregiver. This wonderful little girl’s brain was deprived of oxygen for an underdetermined length of time – potentially for several minutes – and by the time she was rescued, she had passed into a deep coma. Because her parents are very close to her aunt and uncle (my daughter and her husband), we have had the great pleasure of having this little girl bouncing around our house on many occasions. She is a very special little kid. Chock full of spirit. Agile, athletic, determined. Smart as a whip. Tough as nails.

About a year ago, this little girl fell on the tile steps of our home and broke her arm. We were (of course) horrified. She cried a bit, but stopped crying before she was taken to the emergency room, with her forearm still hanging down at at that odd angle that assures you that an arm is truly broken! A scrappy little monkey, indeed! The next time I saw her, she was bouncing up those very same steps, swinging her cast jauntily, looking for fun, oblivious to the scene of the accident!

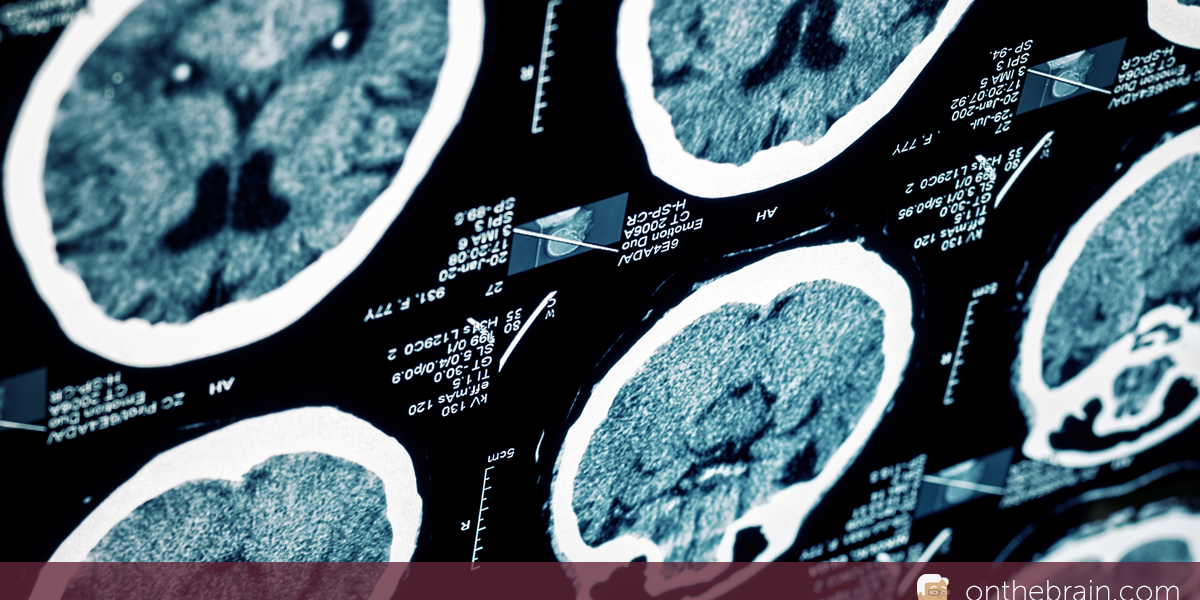

This lively little child came out of her coma after eight days, in a high state of anxiety and distress, not able to talk, highly impaired in her movement control. It is not yet clear if she shall be able to swallow. Her breathing and heart rate are irregular. Although the full picture is still unclear because of medication, it is evident that she has some degree of higher-than-normal muscle tone in the legs, trunk, arms and neck. As in all such cases, brain scans and EEG recordings are difficult to translate into certain loss, but there are clear physical, electrical and functional signs of brain damage.

As we all know, young brains are remarkably resilient. Still, intensive rehabilitation designed to restore functionality shall likely be a significant daily part of this small child’s life for years to come. Our listening and language training strategies (“Fast ForWord”) will almost certainly be helpful to her, in due time. A hundred other strategies and tools shall probably have to be brought to bear. Ultimate outcomes are uncertain.

I wish that there was a manual for parents that could help them get through a crisis like this one. Because we know THESE parents, we DO more completely feel and understand their pain and anguish. Because I can know the details of how the neurology of this sweet little girl has changed, I should be able to help her get better more completely, and a little faster. Toward that end, I thought that it might be helpful for some of you if I described her therapeutic program in detail, as it progresses. As soon as her motor and cognitive picture is clarified, I’ll try to describe the starting point for her rehabilitation, then update this journal outlining the progression of rehabilitation for you about once every month. If this kind of intensive rehabilitation problem targeting the class of impairments that befall an oxygen-deprivation-injured child falls within your domain of expertise, I respectfully ask those of you in the appropriate help professions to help US, by commenting on how you believe our approach might be more effectively targeted, or more complete.

In the meantime, in a local children’s hospital, we’re doing everything possible to perceptually and cognitively stimulate this small child without distressing her, to help ease her path back to the things that she remembers and understands and loves — while her caregivers work just as hard at stabilizing her vital functions, and at quieting the high muscle tone that we know must be brought under control to increase her prospects for a more complete recovery of motor function. May the fates be with us.